Read time: 6 minutes.

This is Part 2 of 3 in our series on how drugs get approved to treat lung cancer. Make sure to read Part 1 on the phases of clinical trials and why they are important for new drug development.

We all want a treatment for lung cancer that is completely safe and entirely effective. While researchers are working toward that goal, the reality is we aren’t there yet. Every treatment we are considering comes with potential benefits and side effects.

The overarching role of clinical trials is to measure the pros and cons of each drug to help us identify the best treatments for people who need them. But how do we measure the success of cancer treatment?

Endpoints are the measurements of success for clinical trials. They are how we determine if a treatment is safe and effective for people. Endpoints are the key measurements that allow a treatment to continue being tested and determine if it will be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Typically, an endpoint is an event or outcome that can be measured objectively to determine whether the new treatment being studied is helpful and effective. Researchers choose endpoints for their clinical trials based on many factors. One of the major considerations is the phase of the clinical trial.

Why Does This Matter?

Understanding the different phases of clinical trials and the endpoints researchers use can help those living with lung cancer, and caregivers, better understand the results of clinical trials. You'll know how a drug was tested and what it means when someone says a trial was "successful." This can lead to better decision-making when comparing treatment options.

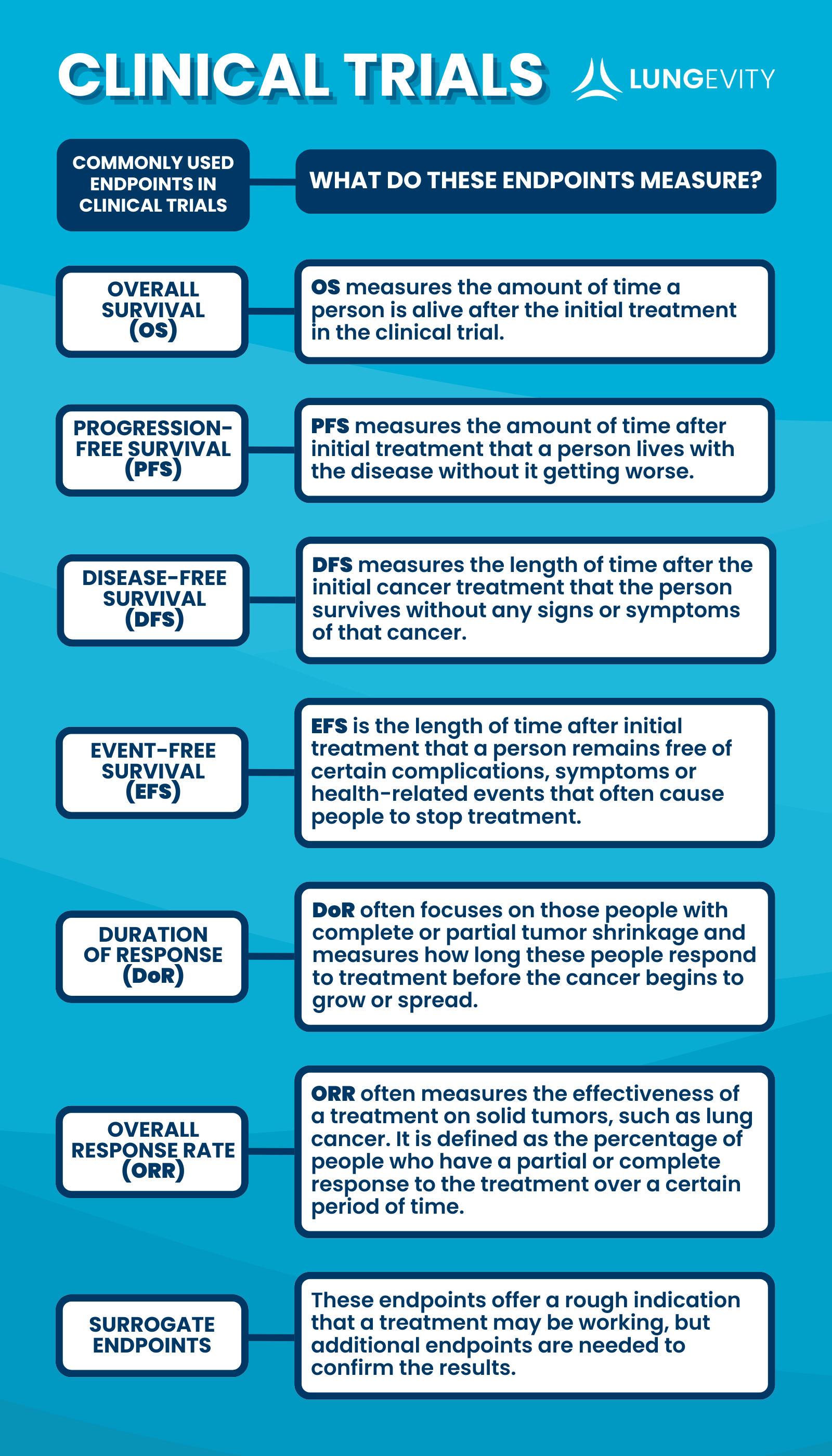

This graphic gives short descriptions of commonly used endpoints. Below the graphic, there's more detail about when and why researchers use these different endpoints.

Overall Survival (OS)

Overall survival is the amount of time a person is alive after the initial treatment on the clinical trial. It’s the gold standard for clinical trial endpoints, being easy to measure and very objective. This metric is typically used in phase 3 or phase 4 clinical trials when the researchers are hoping to use the data to gain or maintain FDA approval. As you can imagine, overall survival is an impressive success metric.

One major downside to relying on overall survival for measuring clinical trial success is that it can take a long time to reach this endpoint. The longer the trial, the more expensive it gets.

To keep costs down, speed up the process, and get a more nuanced understanding of treatment effectiveness, researchers have been using other types of endpoints in place of (or in addition to) overall survival. These are explained below.

Progression-Free Survival (PFS)

Progression-free survival is the amount of time after initial treatment that a patient lives with the disease without it getting worse. This is a popular endpoint used in early (phase 2) clinical trials because it requires fewer patients, allows for the early completion of the clinical trial, and reduces the cost of patient follow-ups.

Measuring progression-free survival also offers more detailed information about the short-term effects of the treatment compared to overall survival. One of the main challenges of using progression-free survival as a success metric is that researchers have found that a long progression-free survival doesn’t always mean that a person will live longer. This endpoint is only used for studies of advanced-stage or metastatic cancer.

Disease-Free Survival (DFS)

Disease-free survival measures the length of time after the initial cancer treatment that the patient survives without any signs or symptoms of that cancer. This clinical trial endpoint is very similar to progression-free survival. Both of these endpoints have the benefits of providing quicker results and needing fewer patients enrolled.

Typically, disease-free survival is used when studying early-stage cancer with adjuvant treatment (treatment given after the primary treatment to lower the risk that the cancer will come back), and progression-free survival is used when the trial is studying cancer at later stages. Whenever a clinical trial uses disease-free survival or progression-free survival as an endpoint, it is important that the rules of the clinical trial clearly lay out how to decide if the cancer has started to grow again. As described, this endpoint is only used for early-stage cancer.

Event-Free Survival (EFS)

Event-free survival is very similar to disease-free survival, but it allows patients and researchers to see the many variables that could cause a patient to stop treatment. Event-free survival is the length of time after initial treatment that someone remains free of certain complications, symptoms, or health-related events. Often these events cause doctors to discontinue the treatment. Patients could stop taking the treatment for many reasons, including harsh side effects or the cancer beginning to grow again.

Event-free survival is often used instead of disease-free survival as an endpoint in neoadjuvant clinical trials because in the neoadjuvant setting, patients are being treated before surgery, so they are not yet disease-free. As described, this endpoint is only used for early-stage cancer.

Duration of Response (DoR)

The duration of response endpoint is often used along with other endpoints to help provide a more detailed picture of treatment effects. It focuses only on people with complete or partial tumor shrinkage and measures how long they respond to treatment before the cancer begins to grow or spread.

Overall Response Rate (ORR)

This clinical trial endpoint, sometimes referred to as objective response rate, is a good way to measure the effectiveness of a treatment for solid tumors, such as lung cancer. It is defined as the percentage of patients who have a partial or complete response to the treatment over a certain period of time.

Researchers rely on the RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) criteria as a consistent way to select and measure tumors when using the overall response rate to determine if a tumor is growing or shrinking. This endpoint is often used in clinical trials in the neoadjuvant setting to monitor tumor shrinkage before surgery.

Surrogate Endpoints

Particularly important in early-phase clinical trials, surrogate endpoints are indications that a drug may be working. Some surrogate endpoints include tumor shrinkage and reduced levels of a biomarker in the blood. The endpoints help researchers quickly evaluate the potential effectiveness of a treatment, but they aren’t as reliable as other endpoints, such as overall survival or progression-free survival.

Continue learning how new drugs get approved to treat lung cancer by reading the final part of this series—How Do Drugs Get Approved (and Fast-Tracked) by the FDA?

If you like this type of information and want more of it, make sure to sign up for our email list.