Immunotherapy for lung cancer is a type of treatment that aims to enhance the body’s immune response and stop the lung cancer from evading the immune system. Immunotherapy does not treat the lung cancer directly.

Find out more about how the immune system works, how treatments to boost it can help fight lung cancer, and whether participating in a clinical trial using immunotherapy might be a good option for you.

What is the immune system?

The immune system is a complex network of cells, tissues, and organs that work together to protect the body from foreign invaders, such as bacteriaA large group of single-cell microorganisms. Some cause infections and disease in animals and humans or virusesA very simple microorganism that infects cells and may cause disease. The key players in defending the body are a specific type of white blood cellA type of blood cell that helps the body fight infection and other diseases called lymphocytes. There are three types of lymphocytes: B cellsA type of white blood cell that circulates in the blood and lymph seeking out foreign invaders, T cellsA type of white blood cell that helps protect the body from infection and may help fight cancer, and natural killer (NK) cellsA type of white blood cell that patrols the body and is on constant alert, seeking foreign invaders.1,2

The immune system is a complex network of cells, tissues, and organs that work together to protect the body from foreign invaders, such as bacteriaA large group of single-cell microorganisms. Some cause infections and disease in animals and humans or virusesA very simple microorganism that infects cells and may cause disease. The key players in defending the body are a specific type of white blood cellA type of blood cell that helps the body fight infection and other diseases called lymphocytes. There are three types of lymphocytes: B cellsA type of white blood cell that circulates in the blood and lymph seeking out foreign invaders, T cellsA type of white blood cell that helps protect the body from infection and may help fight cancer, and natural killer (NK) cellsA type of white blood cell that patrols the body and is on constant alert, seeking foreign invaders.1,2

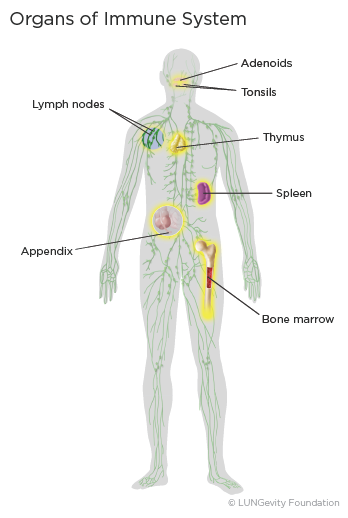

Lymphocytes grow and develop in the bone marrowThe soft, sponge-like tissue in the center of most bones, thymusAn organ in the chest behind the breastbone that is part of the lymphatic system, in which T lymphocytes grow and multiply, and spleenAn organ on the left side of the abdomen near the stomach that makes lymphocytes, filters the blood, stores blood cells, and destroys old blood cells. They can also be found in clumps throughout the body, primarily as lymph nodesA rounded mass of lymphatic tissue surrounded by a capsule of connective tissue. Clumps of lymphoid tissue are also found in the appendix, tonsils, and adenoidsA mass of lymphatic tissue located where the nose blends into the throat. The lymphocytes circulate through the body between the organs and nodes via lymphatic vesselsThin-walled tubular structures that collect and filter lymph fluid before transporting it back to the blood circulation and blood vessels. In this way, the immune system works in a coordinated manner to monitor the body for germs and other abnormal cells.2,3,4,5

How does the immune system work?

A key feature of the immune system is its ability to tell the difference between the body's own normal cells, or "self," and cells and other substances that are foreign to the body, or "non-self." Every cell in the body carries a set of distinctive proteinsMolecules made up of amino acids that are needed for the body to function properly on its surface. These identifying surface proteins let the immune system know that they are cells that belong to the body.5,6 They can be compared to the uniforms a football team wears. In the same way the uniform helps the quarterback know who is on his team, the proteins let the immune system know which cells belong in the body.

Healthy cells display normal proteins on their surface. The immune system has learned to ignore normal proteins. If the surface proteins are abnormal, such as when a virus infects cells or when cells become cancerous, they can be recognized by the immune system. Proteins recognized by the immune system are called antigensA protein on the surface of a cell that causes the body to make a specific immune response.5,6

If a foreignSomething that comes from outside the body substance—such as a bacteria, virus, or tumorAn abnormal mass of tissue that results when cells divide more than they should or do not die when they should cell—is recognized, the immune system kicks in to try to deal with it. It is the “non-self” antigens on the surface of these cells—the other team’s uniform—that the immune system identifies as abnormal. The immune system is great at recognizing bacteria and virus cells, because they "look" very different from healthy cells. On the other hand, tumor cells started as healthy cells and can look a lot like healthy cells. As a result, the body may have a harder time recognizing tumor cells as foreign.5,6

In other instances, the immune system may recognize a tumor antigen but may be unable to mount a response strong enough to destroy the tumor. As cancers grow, they can evolve ways to escape from attack by the immune system. For these reasons, many people with healthy immune systems still develop cancer, and cancer still progresses. In many people with cancer, the cancer cells coexist with immune cells capable of killing the cancer, but the cancer cells hold the immune cells back from working the way they should.5,6

How does the immune system combat cancer?

The immune system has two responses that work together to detect and destroy cancer cells: innate immune responseImmune response to a pathogen that involves the pre-existing defenses of the body and adaptive immune response.

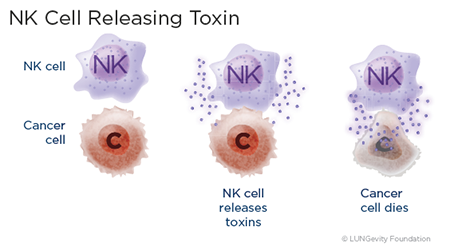

The innate immune response is the first line of defense. The innate immune system’s normal function is to protect the body from initial invasion by bacteria and viruses, such as when bacteria invade broken skin or viruses land in the throat. The system includes natural killer (NK) cells, a type of lymphocyte that patrols the body and is on constant alert, looking for foreign invaders and abnormal cells. If cells from the innate immune system recognize a cancer cell as abnormal, they can attach to it and immediately release toxic chemicals that kill it. NK cells and other cells of the innate immune system do not need to recognize a specific abnormality on a cell to be able to do their job2,5.6

The innate immune response is the first line of defense. The innate immune system’s normal function is to protect the body from initial invasion by bacteria and viruses, such as when bacteria invade broken skin or viruses land in the throat. The system includes natural killer (NK) cells, a type of lymphocyte that patrols the body and is on constant alert, looking for foreign invaders and abnormal cells. If cells from the innate immune system recognize a cancer cell as abnormal, they can attach to it and immediately release toxic chemicals that kill it. NK cells and other cells of the innate immune system do not need to recognize a specific abnormality on a cell to be able to do their job2,5.6

If the bacteria, viruses, or cancer cells evade the innate response, then the adaptive immune response becomes active. The adaptive immune response recognizes specific abnormalities on cancer cells that make them different from the cells that are naturally found in the body. Though it is more effective than the innate immune response, the adaptive immune response takes longer to become activated. The cells of the adaptive immune response include the other two types of lymphocytes: B cells and T cells.6

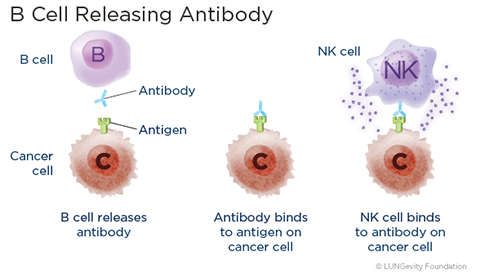

B cells are like the body's military intelligence system, seeking out their targets and sending defenses to lock onto them. They react to “non-self” antigens by making proteins called antibodiesA protein made by B cells in response to an antigen, the purpose of which is to help destroy the antigen. Antibodies are proteins that can attach to foreign and abnormal cells and let the body know that they are dangerous. Antibodies can kill cancer cells in several ways, including binding natural killer (NK) cells to the cancer. B cells can create "memory"—they start to make antibodies quickly when they recognize a past antigen.2,5,6

B cells are like the body's military intelligence system, seeking out their targets and sending defenses to lock onto them. They react to “non-self” antigens by making proteins called antibodiesA protein made by B cells in response to an antigen, the purpose of which is to help destroy the antigen. Antibodies are proteins that can attach to foreign and abnormal cells and let the body know that they are dangerous. Antibodies can kill cancer cells in several ways, including binding natural killer (NK) cells to the cancer. B cells can create "memory"—they start to make antibodies quickly when they recognize a past antigen.2,5,6

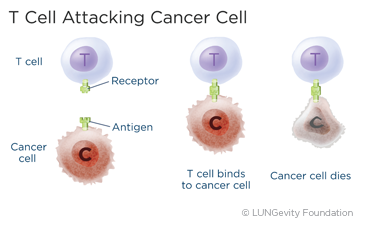

T cells are the major cells the body uses to recognize and destroy abnormal cells. Once a foreign antigen or abnormal cancer protein has been recognized by T cells, the T cells rapidly increase in number. An army of T cells can be formed; these T cells are specifically designed to attack and kill cells that have foreign antigens.2,5,6

The T cells are like soldiers, destroying the invaders. They are responsible for coordinating the entire immune responseThe activity of the immune system against foreign substances (antigens) and destroying infected cells and cancer cells. T cells can also create memory after an initial response to an antigen. This memory is meant to ensure that the attack on cancer cells can keep going in the long term, for months or longer. The memory also allows for future responses against the specific abnormal antigen on cancer cells, if and when the cancer comes back.2,5,6

The T cells are like soldiers, destroying the invaders. They are responsible for coordinating the entire immune responseThe activity of the immune system against foreign substances (antigens) and destroying infected cells and cancer cells. T cells can also create memory after an initial response to an antigen. This memory is meant to ensure that the attack on cancer cells can keep going in the long term, for months or longer. The memory also allows for future responses against the specific abnormal antigen on cancer cells, if and when the cancer comes back.2,5,6

If the immune system recognizes the lung tumor cells and can destroy them, why are lung tumors able to grow? Research has shown that some tumors enable their own growth by turning off the immune response. Immune responses beyond what is normal or necessary can be toxic, so T cells have many normal methods to dampen themselves down and essentially turn themselves off. This may allow the growth and development of tumor cells despite the presence of T cells with the potential to kill cancer cells. Researchers are working to understand exactly how this happens and how best to turn the cancer-killing T cells back on.2,5,6

What is immunotherapy?

Biological therapies use substances made from living organisms to treat disease. These substances either already exist in nature or are manmade in a laboratory.7

Immunotherapy is considered a type of biological therapyA type of treatment that uses substances made from living organisms to treat disease. It aims to enhance the body’s immune response and stop lung cancers from escaping from the immune system. Immunotherapy is a treatment that strengthens the natural ability of the patient’s immune system to fight cancer. Instead of targeting the person’s cancer cells directly, immunotherapy trains a person’s natural immune system to selectively target and kill cancer cells, either by suppressing factors that block the immune system or by enabling the immune system to mount or maintain a response.5,6

Of the three main types of immunotherapy drugs that are currently being studied in people with lung cancer—immune checkpoint inhibitors, therapeutic cancer vaccines, and adoptive T cell transfer—immune checkpoint inhibitors have made the most progress at this time. All of the currently approved FDA-approved immunotherapy drugs for lung cancer are checkpoint inhibitors.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

What is an immune checkpoint pathway?

Many lung cancers coexist with T cells capable of killing the cancer cells. However, the immune system has many normal mechanisms for dampening itself down. The immune system has fail-safe mechanisms that are designed to suppress the immune response at appropriate times in order to minimize damage to healthy tissue. These mechanisms are called immune checkpoint pathways. They are essentially the brakes on the immune system.

The PD1/PD-L1 proteins are an example of an immune checkpoint pathway. The PD-1 protein is found on the T cells and acts as the brakes that keep the T cells from attacking healthy cells. PD-L1 is a protein on healthy cells, but it can also be found on cancer cells. When the PD-1 on T cells attaches to the PD-L1 on other cells, the T cells know not to attack those other cells. Cancer cells can thus evade detection by T cells, with the result that the T cells' immune response is lessened at a time when it should be active. This allows cancer cells to thrive.8

How do immune checkpoint inhibitors work?

The immune checkpoint inhibitors work by targeting and blocking the fail-safe mechanisms of the immune system. Their goal is to block the immune system from limiting itself, so that the original anti-cancer response works better.9

What immune checkpoint inhibitors are FDA-approved?

There are currently six FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors for treating patients with lung cancer. All of them have indications for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Two of them also have indications for small cell lung cancer (SCLC) patients. Specifically:

- Atezolizumab (Tecentriq®):10

- Approved for first-line treatment of adult patients with metastatic NSCLC whose tumors have high PD-L1 expression (PD-L1 stained ≥ 50% of tumor cells [TC ≥ 50%] or PD-L1 stained tumor infiltrating immune cells [IC] covering ≥ 10% of the tumor area [IC ≥ 10%]), with no EGFR or ALK genomic tumor aberrations

- Approved for first-line treatment of adult patients with metastatic non-squamous NSCLC with no EGFR or ALK mutations, in combination with paclitaxel protein-bound and carboplatin

- Approved for first-line treatment of adult patients with metastatic non-squamous NSCLC with no EGFR or ALK mutations, in combination with bevacizumab, paclitaxcel, and caboplatin

- Approved for adult patients with metastatic NSCLC whose lung cancer has progressed during or after being treated with platinum-contatining chemotherapy. Patients with EGFR or ALK mutations should have disease progression on FDA-approved therapy for these mutations before receiving this drug

- Approved for first-line treatment of adult patients with extensive-stage SCLC, in combination with carboplatin and etoposide

- Approved for adjuvant treatment following resection (surgery) and platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with stage II to IIIa NSCLC whose tumors have PD-L1 expression on ≥ 1% of tumor cells, as determined by an FDA-approved test

- Cemiplimab-rwlc (Libtayo®):11

- Approved for first-line treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC—either (1) locally advanced who are not candidates for surgical resection or definitive chemoradiation or (2) metastatic—whose tumors have high PD-L1 expression (tumor proportion score [TPS] ≥ 50%), as determined by an FDA-approved test, with no EGFR, ALK, or ROS1 mutations

- In combination with platinum‐based chemotherapy for the first‐line treatment of adult patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with no EGFR, ALK or ROS1 aberrations and is:

- locally advanced where patients are not candidates for surgical resection or definitive chemoradiation or

- metastatic

- Durvalumab (Imfinzi®):12

- Approved for patients with stage III NSCLC whose tumors are not able to be surgically removed and whose cancer has not progressed after treatment with concurrent platinum-based chemotherapy and radiation therapy. (The purpose of this treatment is to reduce the risk of the lung cancer progressing.)

- Approved for first-line treatment of adult patients with extensive-stage SCLC, in combination with etoposide and either carboplatin or cisplatin

- Approved in combination with tremelimumab-actl and platinum-based chemotherapy, for the treatment of adult patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with no sensitizing epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) genomic tumor aberrations

- Approved in combination with platinum-containing chemotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment, followed by durvalumab continued as a single agent as adjuvant treatment after surgery, for the treatment of adult patients with resectable (tumors ≥ 4 cm and/or node positive) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and no known epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangements.

- Approved as a single agent, for the treatment of adult patients with limited-stage small cell lung cancer (LS-SCLC) whose disease has not progressed following concurrent platinum-based chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

- Nivolumab (Opdivo®):13

- Approved in combination with platinum-doublet chemotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment for adult patients with resectable (tumors ≥ 4 cm or node positive) NSCLC

- Approved as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic or recurrent NSCLC and no EGFR or ALK mutations, in combination with ipilimumab and two cycles of platinum-doublet chemotherapy

- Approved as first-line treatment for adult patients with metastatic NSCLC expressing PD-L1 (TPS ≥ 1%) as determined by an FDA-approved test, with no EGFR or ALK mutations, in combination with ipilimumab

- Approved for patients with metastatic NSCLC whose lung cancer has progressed on or after platinum-based chemotherapy. Patients with EGFR or ALK mutations should have disease progression on FDA-approved therapy for these mutations before receiving this drug

- Approved for adult patients with resectable (tumors ≥4 cm or node positive) NSCLC and no known EGFR mutations or ALK rearrangements, for neoadjuvant treatment, in combination with platinum-doublet chemotherapy, followed by single-agent nivolumab as adjuvant treatment after surgery.

- Pembrolizumab (Keytruda®):14

- Approved as a single agent for first-line treatment of patients with 1) stage III NSCLC who are not candidates for surgery or definitive chemoradiation or 2) metastatic NSCLC, and whose tumors express PD-L1 and have a TPS ≥ 1%, as determined by an FDA-approved test, with no EGFR or ALK mutations

- Approved as a single agent for patients with metastatic NSCLC whose tumors express PD-L1 (TPS ≥ 1%), as determined by an FDA-approved test, with disease progression on or after platinum-containing chemotherapy. Patients with EGFR or ALK mutations should have disease progression on FDA-approved therapy for these mutations before receiving this drug.

- Approved as first-line treatment of patients with metastatic non-squamous NSCLC with no EGFR or ALK mutations, in combination with pemetrexed and platinum chemotherapy

- Approved a first-line treatment of patients with metastatic squamous NSCLC, in combination with carboplatin and either paclitaxel or paclitaxel protein-bound

- Approved for the treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic tumor mutational burden-high (TMB-H) [≥ 10 mutations/megabase] solid tumors, as determined by an FDA-approved test, that have progressed following prior treatment and who have no satisfactory alternative treatment options. TMB is the total number of mutations found in the DNA of cancer cells

- As a single agent, for adjuvant treatment following resection and platinum-based chemotherapy for adult patients with stage IB (T2a ≥4 cm), II, or IIIA NSCLC.

- For the treatment of patients with resectable (tumors ≥4 cm or node positive) NSCLC in combination with platinum-containing chemotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment, and then continued as a single agent as adjuvant treatment after surgery.

- Tremelimumab-actl (Imjudo®)26

- Approved in combination with durvalumab and platinum-based chemotherapy for the treatment of adult patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with no sensitizing epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) genomic tumor aberrations

Patients with pre-existing autoimmune conditions should discuss these conditions with their doctors. Those who do go on an immune checkpoint inhibitor should be monitored very carefully for autoimmune side effects.15

How are immune checkpoint inhibitors administered?

FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors are given intravenouslyInto or within a vein. Dosages, infusion time, and schedules vary, depending on the drug.

- Atezolizumab (Tecentriq®)10 is given over 60 minutes for the first infusion. If the first infusion is tolerated, the remaining infusions may be delivered for 30 minutes.

- As a single agent, it is given until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity in these dosages:

- 1,680 mg every 4 weeks or

- 1,200 mg every 3 weeks or

- 840 mg every 2 weeks

- In combination with chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab, the dosage is 1,200 mg every 3 weeks prior to chemotherapy until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

- Following completion of 4-6 cycles of chemotherapy, and if bevacizumab is discontinued, it is given until progression or unacceptable toxicity in these dosages:

- 1,680 mg every 4 weeks or

- 1,200 mg every 3 weeks or

- 840 mg every 2 weeks

- As a single agent, it is given until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity in these dosages:

- Cemiplimab-rwlc (Libtayo®)11 is given every 3 weeks over 30 minutes in a dosage of 350 mg until disease progression or unaccceptable toxicity

- Durvalumab (Imfinzi®)12 is given over 60 minutes:

- for patients with stage III NSCLC, until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or a maximum of 12 months:

- if the patient's body weight is 30 kg and more: 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks or 1,500 mg every 4 weeks

- if the patient's body weight is less than 30 kg: 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks

- for patients with extensive-stage SCLC, until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity:

- if the patient's body weight is 30 kg and more: 1,500 mg in combination with chemotherapy every 3 weeks for 4 cycles, followed by 1,500 mg every 4 weeks as a single agent

- if the patient's body weight is less than 30 kg: 20 mg/kg in combination with chemotherapy every 3 weeks for 4 cycles, followed by 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks as a single agent

- for patients with stage III NSCLC, until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or a maximum of 12 months:

- Nivolumab (Opdivo®)13 is given:

- in the neoadjuvant setting: 360 mg with platinum-doublet chemotherapy on the same day every 3 weeks for 3 cycles

- as a single agent for metastatic NSCLC: over 30 minutes, 240 mg every 2 weeks or 480 mg every 4 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity

- for metastatic NSCLC that expresses PD-L1 and given in combination with ipilimumab: 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks over 30 minutes with ipilimumab 1 mg/kg every 6 weeks over 30 minutes, until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or up to 2 years in patients without disease progression

- for metastatic or recurrent NSCLC and given in combination with ipilimumab and chemotherapy: 360 mg every 3 weeks over 30 minutes with ipilimumab 1 mg/kg every 6 weeks over 30 minutes, and two cycles of histology-based platinum doublet chemotherapy every 3 weeks, until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or up to 2 years in patients without disease progression

- for neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment of resectable NSCLC: Neoadjuvant treatment of 360 mg every 3 weeks with platinum-doublet chemotherapy on the same day every 3 weeks for up to four cycles or until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity, followed by adjuvant treatment as a single agent of 480 mg every 4 weeks after surgery for up to 13 cycles (approximately 1 year) or until disease recurrence or unacceptable toxicity

- Pembrolizumab (Keytruda®)14 is given over 30 minutes, and is given until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or up to 24 months:

- when it is given as a single agent: 200 mg every 3 weeks or 400 mg every 6 weeks

- when it is given in combination with chemotherapy: 200 mg every 3 weeks or 400 mg every 6 weeks, with pembrolizumab (Keytruda®) given prior to chemotherapy when given on the same day

How well do immune checkpoint inhibitors work?

Patients whose tumors have high levels of PD-L1 expression are more likely to respond to PD-1/PD-L1 therapies. However, even those with tumors that do not express PD-L1 may respond to these treatments.

Not all advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients who are administered immunotherapy respond to it. However, in certain circumstances, the response rate can be high: the response rate to pembrolizumab (Keytruda®) as monotherapy for first-line treatment of tumors with high PD-L1 expression has been shown to be about 40%.16

The response may continue after treatment is stopped. Patients may have long-lasting remission.17

Researchers are studying how to increase the number of people who respond to this treatment. In clinical trialsA type of research study that tests how well new medical approaches work in people, they are combining treatments, boosting the immune system, and using other strategies.

How long does it take to see results from therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors?

Of those patients in clinical trials with immune checkpoint inhibitors who have responded, most respond within the first six to eight weeks.18

In a very small subset of patients (1%-3%), the tumor on a CT scanA procedure that uses a computer linked to an X-ray machine to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body may seem to get worse at first and then get better, or there may seem to be new areas of tumor. One theory about this is that the tumors get larger because a large number of the patient’s T cells move into the tumor to attack and kill the cancer cells. For the great majority of patients whose scans show worsening of disease after at least a couple of months on immunotherapy, the scans are accurately showing that the immunotherapy is not working.18

In cases like this, the best course of action will likely be based on a number of factors. If the patient’s scan looks worse but the person is feeling fine, the doctor and patient may decide together to do another course of immunotherapy. If the scan looks worse and the person is feeling worse, then it may not make sense to continue with this type of therapy. In this case, the patient may need another kind of therapy to control the symptoms.

Managing side effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors

Side effects from lung cancer treatment are common, but just because a side effect is common does not mean that a patient will experience it. Before beginning treatment, the patient should discuss with the healthcare team what side effects might be expected from immune checkpoint inhibitors and how to prevent or ease them. The patient should speak with the healthcare team if and when new side effects begin, as treating them early on is often more effective than trying to treat them once they have already become severe; in addition, it needs to be determined whether the side effects are related to treatment or not. What side effects are being experienced may impact future treatment plans. Although most side effects go away when treatment is over, some can last a long time.

Common side effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors as a group include.10,11,12,13,,14

- Fatigue

- Nausea

- Cough

- Difficulty in breathing

- Constipation

- Musculoskeletal pain

- Rash

- Decreased appetite

Rarer but more serious side effects, such as pneumonitis and other inflammatory conditions, may also occur.

Some patients experience side effects that are severe enough that they need to stop taking the immunotherapy treatment. In general, based on what has been seen to date, these kinds of treatments are well tolerated by most patients.

What new immune checkpoint inhibitors are currently being tested?

A number of immune checkpoint inhibitor drugs not yet approved for lung cancer are currently being tested, including:19

| Generic Name | Brand Name | Types of lung cancer being studied |

|

Avelumab |

Bavencio® |

NSCLC, SCLC |

|

PDR001 (spartalizumab) |

To be determined |

NSCLC |

Learn more about clinical trials here.

Bi-specific T-cell engagers

►What is a bi-specific T-cell engager?

A bi-specific T-cell engager is a novel type of engineered molecule used for the treatment of cancer. These molecules harness and activate T-cells, which are involved in the body’s immune response, to attack tumor cells.

►How do bi-specific T-cell engagers work?

T-cells are activated by the immune system when a foreign antigen or abnormal cancer protein has been recognized in the body. In general, human antibodies are monospecific, which means that they recognize only one antigen. However, bi-specific antibodies (bsAbs) are unique molecules that can bind to more than one antigen or protein simultaneously. Bi-specific T-cell engagers work by binding directly to a receptor found on the T-cell and an antigen found on the cancer cell. The binding of these two cells allows the T-cell to recognize and attack the tumor.27,28

►What bi-specific T-cell engagers are FDA-approved?

There is currently one FDA-approved bi-specific T-cell engager for treating patients with small cell lung cancer:

- Tarlatamab-dlle (ImdelltraTM)29

- Approved for the treatment of adult patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC) with disease progression on or after platinum-based chemotherapy.

►Managing side effects of bi-specific T-cell engager treatment

Side effects of bi-specific T-cell engager treatment vary by patient. Some common side effects include29:

- Cytokine release syndromeA collection of symptoms including fever, nausea, headache, rash, rapid heartbeat, low blood pressure, and trouble breathing

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Altered or impaired sense of taste

- Decreased appetite

- Musculoskeletal pain

- Constipation

- Anemia

- Nausea

Therapeutic cancer vaccines

What is a therapeutic cancer vaccine?

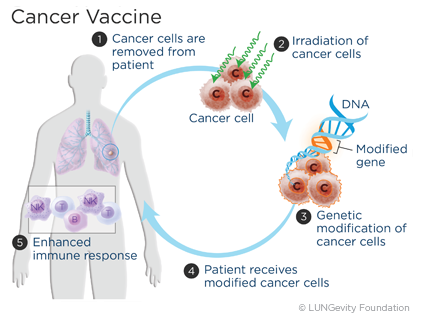

When most people think of a vaccine, they think of a traditional vaccine given to prevent an infectious disease, such as measles, polio, or COVID-19. In addition to the traditional vaccines, there are two types of cancer vaccines. A preventive cancer vaccine is given to prevent cancer from developing in healthy people. For example, the hepatitis B vaccine is given to children to protect against a hepatitis B viral infection, which can lead to liver cancer. In contrast, a therapeutic cancer vaccine is given to treat an existing cancer by causing a stronger and faster response from the immune system. Most commonly, they are used in patients in remission in an attempt to prevent likely relapseThe return of a disease or the signs and symptoms of a disease after a period of improvement or the cancer from returning.20,21,22 Therapeutic cancer vaccines are being studied in lung cancer patients. There are currently no FDA-approved therapeutic cancer vaccines for patients with lung cancer.

How do therapeutic cancer vaccines work?

A therapeutic cancer vaccine is made from a patient’s own tumor cells or from substances taken from the tumor cells. They are designed to work by activating the cells of the immune system to recognize and act against the specific antigen on the tumor cell. Because the immune system has special cells for memory, the hope is that the vaccines will also help keep the lung cancer from coming back.20,21,22

A therapeutic cancer vaccine is made from a patient’s own tumor cells or from substances taken from the tumor cells. They are designed to work by activating the cells of the immune system to recognize and act against the specific antigen on the tumor cell. Because the immune system has special cells for memory, the hope is that the vaccines will also help keep the lung cancer from coming back.20,21,22

Adoptive T cell transfer

What is adoptive T cell transfer?

What is adoptive T cell transfer?

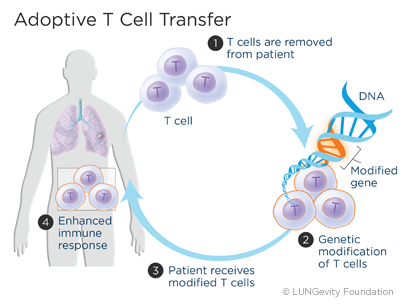

The goal of adoptive T cell transfer is to improve the ability of a person’s own T cellsA type of white blood cell to fight cancer. For lung cancer, this approach is still being developed. There are currently no FDA-approved adoptive T cell transfer treatments for patients with lung cancer.

In adoptive T cell transfer, a sample of T cells is removed from the patient and then genetically changed in order to make the T cells more active against specific cancer cells. Scientists can change what is on the surface of the T cells. For example, they can add a receptor to the surface of the T cell that will target a specific antigen on a cancer cell. The receptors work like very specific Velcro that allows T cells to stick to cancer cells and kill the cells. The T cells are then returned to the patient, and the altered T cells quickly home in on their targets.23,24,25

How does adoptive T cell transfer work?

Typically during an immune response, T cells multiply. After the initial response, most of the newly made T cells are eliminated. This keeps the total T cell number in the body at a normal level. The normal level of T cells is usually not high enough to sustain a response strong enough to effectively fight cancer.23,24,25

However, there is evidence that T cells have the ability to multiply in abundance when given to someone whose immune system has been weakened. Therefore, in an adoptive T cell transfer, patients are given chemotherapy prior to the adoptive T cell transfer in order to suppress their immune system. Once the chemotherapy is completed and the immune system is weakened, hundreds of millions of modified T cells are reintroduced into the patient. The goal of the T cell transfer is to enable the immune system to attack the tumors in a large number that is otherwise impossible and in a way that it is incapable of doing on its own.23,24,25

how are t cells removed from and returned to a patient?

The three approaches to performing adoptive T cell transfer are:25

- Taking T cells from the body and changing them with special receptors, called chimeric antigen receptors (CARs). CARs recognize specific proteins found on the surface of cancer cells. The CAR T cells then bind to the cancer cells that have those proteins and destroy them

- Collecting a sample from the actual tumor and multiplying the T cells in a laboratory

- Taking T cells from the bloodstream through a procedure called leukapheresisRemoval of the blood to collect specific blood cells; the remaining blood is returned to the body and genetically altering them to attack cancer cells that have specific antigensA protein on the surface of a cell that causes the body to make a specific immune response

After any of these, the T cells are then returned to the patient through an infusionA method of putting fluids, including drugs, into the bloodstream.23,24,25

Finding a clinical trial that might be right for you

Clinical research is ongoing to evaluate the role of immunotherapy approaches, alone or in combination with other treatments.19

If you are considering participating in a clinical trial, start by asking your healthcare team whether there is one for which you might qualify in your area. In addition, there are several resources to help you find one that may be a good match for you.

LUNGevity partners with Carebox, a clinical trials matching service, to help you with the decision of whether to participate in a clinical trial. Carebox helps you identify which lung cancer clinical trials you may be eligible for. The clinical trial navigators can also guide you through the process of getting enrolled if you choose to take part in a clinical trial. Clinical trial navigators are available Monday through Friday from 9:00 am to 5:00 pm ET at 877-769-4834 (in both English and Spanish). Learn more about this free service and even fill out an online profile to help identify clinical trials that might be a good match for you.

Information about available clinical trials is also available through these websites:

- National Cancer Institute clinical trials search: This site includes all of the thousands of clinical trials in the United States in all cancer types.

- My Cancer Genome: This resource is managed by a team of doctors at Vanderbilt University. My Cancer Genome gives up-to-date information on what mutations make cancers grow and related treatment options, including available clinical trials.

- Lung Cancer Master Protocol (Lung-MAP): For patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer, Lung-MAP is a collaboration of many research sites across the country, using a unique approach to matching patients to one of several drugs being developed.

Updated December 12, 2024

References

- Vaccines Protect You. vaccines.gov website. https://www.vaccines.gov/basics/work/prevention/index.html. Reviewed March 2020. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- Silva, JC. What are lymphocytes and what are healthy levels to have? Medical News Today website. https://medicalnewstoday.com/articles/320987.php. Reviewed January 13, 2020. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- Zimmerman, A. Lymphatic System: Facts, Functions, & Diseases. LiveScience.com website. https://www.livescience.com/26983-lymphatic-system.html. Posted February 21, 2018. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- Lymphocyte. Encyclopaedia Brittanica website. https://www.britannica.com/science/lymphocyte. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- How does the immune system work? InformedHealth.org website. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279364/. Updated April 23, 2020. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- Overview of the Immune System. Merck Manual Consumer Version website. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/immune-disorders/biology-of-the-immune-system/overview-of-theimmune-system. Revised April 2020. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- Biological Therapy. NCI Dictionary of Cancer Term website. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/biological-therapy. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- PD-1. NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms website. www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/pd-1. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- Understanding Immunotherapy. Cancer.Net website. https://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/how-cancer-treated/immunotherapy-and-vaccines/understanding-immunotherapy. Approved May 2020. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- Tecentriq® (atezolizumab) injection [package insert]. Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, CA; 2016. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/761034s028lbl.pdf. Revised July 2020. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- Libtayo® (cemiplimab-rwlc) injection [package insert]. Regneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Tarrytown, NY. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/761097s014lbl.pdf Accessed November 9, 2022.

- https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/761069s049lbl.pdf. Revised December 2024. Accessed December 5, 2024.

- www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/125554s127lbl.pdf. Revised October 2024. Accessed October 3, 2024.

- Highlights of Keytruda prescribing information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/125514s139lbl.pdf. Revised October 2023. Accessed October 20, 2023.

- Davis EJ and Johnson, DB, Is Immunotherapy Safe in Patients with Autoimmune Disease? ASCO Daily News website. https://dailynews.ascopubs.org/do/10.1200/ADN.19.190252/full/. Posted May 22, 2019. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- Correspondence with Edward B. Garon, MD, UCLA, July 21, 2019.

- Immunotherapy for Lung Cancer. Cancer Research Institute website. https://www.cancerresearch.org/immunotherapy/cancer-types/lung-cancer. Updated November 2020. Accessed March 11, 2021.

- Garon E. Time to Response to Immunotherapy and the Concept of Pseudoprogression. Global Resource for Advancing Cancer Education website. http://cancergrace.org/lung/files/2015/12/GCVL-LU-Immunotherapy_Response_Time_and_Pseudoprogression-Concept.pdf. Posted December 15, 2015. Accessed March 11, 2021.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. US National Institutes of Health website. https.clinicaltrials.gov. Accessed March 11, 2021.

- Cancer Vaccines. and Their Side Effects. American Cancer Society website. https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/treatment-types/immunotherapy/cancer-vaccines.html. Reviewed January 8, 2020. Accessed March 11, 2021.

- What are Cancer Vaccines? Cancer.Net website. https://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/how-cancer-treated/immunotherapy-and-vaccines/what-are-cancer-vaccines. Approved August 2020. Accessed March 11, 2021.

- Cancer Treatment Vaccines. National Cancer Institute website. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types/immunotherapy/cancer-treatment-vaccines. Posted September 24, 2019. Accessed March 11, 2021.

- T-cell Transfer Therapy. National Cancer Institute website. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types/immunotherapy/t-cell-transfer-therapy. Updated August 25, 2020. Accessed March 11, 2021.

- CAR T-Cell Therapy: Engineering Patients' Immune Cells to Treat Their Cancers. National Cancer Institute website. http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/research/car-t-cells#side-effects. Updated July 30, 2019. Accessed March 11, 2021.

- Balch CM, Kaufman HL (eds). Understanding Cancer Immunotherapy, Fifth Edition. Overland Park, KS. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) and PRP Patient Resource Publishing, 2018. . https://www.sitcancer.org/HigherLogic/System/DownloadDocumentFile.ashx?DocumentFileKey=567abb47-c7f1-2fa3-b008-053953020940&forceDialog=0#page=1&zoom…. Accessed March 11, 2021.

- Imjudo® (tremelimumab-actl) injection [package insert]. AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Wilmington, DE. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/761270s000lbl.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2022.

- Bispecific antibody. NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms website. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/bispecific-antibody. Accessed June 5, 2024.

- Zhou S, Liu M, Ren F, et al. The landscape of bispecific T cell engager in cancer treatment. Biomark Res. 9, 38 (2021). doi.org/10.1186/s40364-021-00294-9. Accessed June 5, 2024.

- ImdelltraTM (Tarlatamab-dlle) injection [package insert]. Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen Inc. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/761344s000lbl.pdf. Revised May 2024. Accessed June 5, 2024.